In the Chinese club music underground, there is a nice but influential group of

producers

DJs

visual artists

designers

promoters

club owners

curators

fashion designers

and more –– who coalesce around and catalyze an audio-visual, what might be called, ecosystem, or more plainly, scene. Represented by the scenes growing out of ALL club in Shanghai, OIL in Shenzhen, AXIS and CUE in Chengdu, as well as nightclubs in Hangzhou, Beijing, and Xi’an, there’s a rich cross-pollination between a particular style of electronic music and a particular visual language. And so, I want to ask: What characterizes this ecosystem, how has it developed, who is involved, and what does the future hold?

I have certain insecurities about attempting to pin down a genealogy and topology of this audio-visual scene, not least of all as a white male in China seeking to write about aspects of its culture, as well as the fact that I haven’t been involved anywhere near as long as many others, and also a more general feeling of resistance to trying to capture aspects of a club scene whose strengths seem to lie in the intangible. “How do you write a history of a culture that is fundamentally amnesiac and non-verbal?” 1Simon Reynolds, Energy Flash: A Journey through Rave Music and Dance Culture, (London: Soft Skull Press, 2012), p. 36. At the very least, I can remember some things, I can speak! I want to utilize some of my own experiences of this club scene as a loose basis from which to look at its broader development.

When I first started hitting the clubs in China it was perhaps a moment of change (although not in Chongqing where I was living, with its tiny scene of DJs and promoters focused on European Techno). In 2016, I was in Shanghai and went to The Shelter for the second time (the first visit a hazy mess in 2014). Seeing DJ Lag the South African Gqom trailblazer was a revelation, up until that point isolated in Chongqing, I had little idea that the music that I considered to be leading some kind of electronic sonic avant-garde had a place here and that it was sited in a superlative—underground, dingy and dirty—club space. Being an avid fanboy, I went to Xingfu Lu in the middle of the day just because Kode9 had named a track after the street and to see DADA from the outside. The Shelter was forced to close later that year. But a new sonic world seemed also to have opened up: An inward turn to China-based, and especially Chinese, producers and DJs. 2016 also marked the first release from Shanghai stalwart label Genome 6.66Mbp, a compilation whose influence on the future development of this scene cannot be understated and part also of an important sonic lineage that takes us up to today. And where are we today? It’s a disservice to the unique qualities of each producer to grasp essentialism, but crudely put, it’s a burgeoning underground electronic club music that pushes a fast-paced, brash, crowded sonic palette, metallic and industrial, varied in borrowings and influences. 2Carmen Herold, ‘China’s Sonic Fictions: Music, Technology, and the Phantasma of a Sinicized Future’, SFRA Review, vol. 50, no. 2-3. This essay provides a more detailed characterization of some of the sonic qualities of this Chinese scene, and although there’s not enough space here, Herold’s discussion of the ways in which this scene can intuitively and intrinsically elide censorship is also relevant. For a more general relevant discussion of these sonic qualities see also: Matthew Phillips, ‘2015: The Neofuturist Aesthetic: Technology and counter future in the electronic avant-garde’, Tiny Mixtapes, 12/2015, link. Producers such as Hyph11E, 33EMYBW, Gooooose, GG Lobster, Laughing Ears, Alex Wang and Osheyack are representative of this sound, connected as it is, to a wider global decentralized brand of electronic music that defines itself as being simultaneously from everywhere and nowhere.

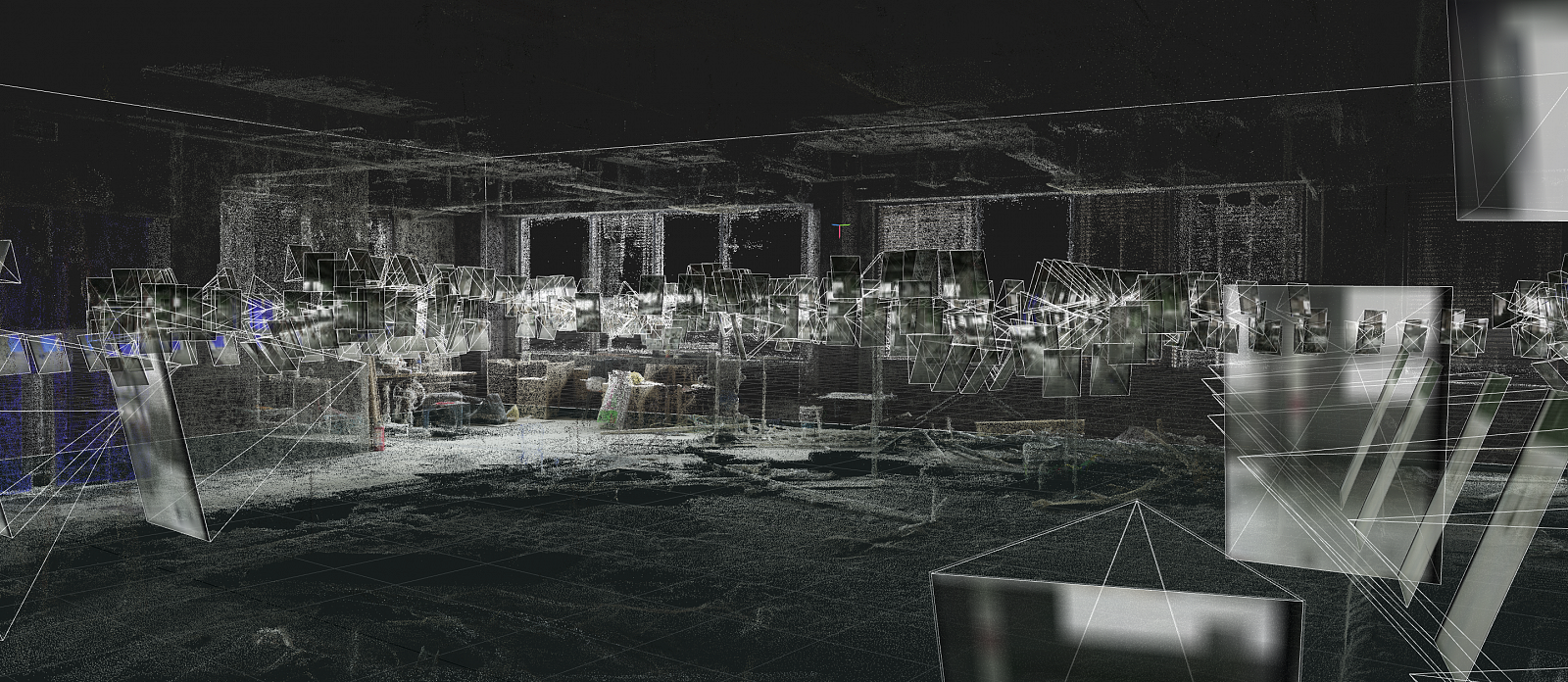

To 2017 and the opening of ALL, The Shelter’s successor, when a whole new local and global attention seemed to have come down onto the scene. By then I’d moved to Beijing and had another moment of bliss finding the music I valued so much coming out of the speakers at DADA. After first hearing and reading about ALL and its quite significant shift away from the grittiness of The Shelter, I took my next pilgrimage down to Shanghai. It was the first time I’d seen an attempt to give underground club music a proper contemporary home. Besides the shiny metallic furniture, mirrors, clean walls, proper bar, and sparse club space designed to better accommodate for visuals, what drew me in most were the screens. That Kim Laughton, a visual artist, and designer, was behind much of this was also of great interest; for some time, I’d tried to reckon with the relationship between contemporary art/visuality and electronic club music, a crossing that Laughton excels in. ALL struck me as a space that explicitly wanted to synthesize these fields—the signs of a nascent audio-visual club ecosystem. 3Yes, there have been numerous past instances of clubs and contemporary art meeting, just one example among many are the nightclub spaces presented at the ICA, London exhibition ‘Radical Disco: Architecture and Nightlife in Italy, 1965-1975’, but here, I’m suggesting that a new contemporary form (new visual language, new actuality, new formats, etc.) of the meeting of the audio and the visual in the club context is at stake here. The Shelter, also, showed earlier signs of this visual turn with some installations and a projector from as early as 2013, but this became much more reified at ALL.

The key locus for this audio-visual is the large LED screen behind the DJ booth, which offers the possibility for close collaboration between musicians and visual artists. 4The presence of screens doesn’t start and end there, at the entrance of both ALL and OIL are banks of smaller portrait-orientated LED screens for displaying event posters and flyers as well as monthly schedules, these encourage GIF and video flyers more ambitious in design and aesthetic than traditional paper versions. This means either freestyle VJing or the creation of bespoke visual elements to accompany a musicians’ performance, as has recently been the case with Wang Newone and Hyph11E, and earlier, Kim Laughton and Craxxxmurf. The latter was a video-game program created work that allowed crowd members to use a gamepad controller to adjust elements of the piece, such as the camera position or lighting. I remember having the chance to use the gamepad and for a moment feeling that, despite a collection of nerdy European music festivals like Unsound and Berlin Atonal being havens for this audio-visual club world, this Chinese club ecosystem’s foregrounding of the visual is to an extent not seen elsewhere. Having a permanent high-quality screen in such a prominent position is a relatively unique set up, most clubs around the world would be able to cough up an old projector for accompanying visuals if really pushed. As to why we can also point to the relative cheapness of LED screens in China and the advancement of the tech surrounding it. Later, on my first trip to OIL in Shenzhen to DJ at one of its opening events, I found that this new proper contemporary underground club aesthetic was spreading and that the proliferation of the visual via screens was again key. There’s an alluring sense of iconoclasm here also, while many clubs try to dissuade from the use of mobile phones, it’s deliciously ironic to see giant screens in the most prominent position in the club. Now, fresh events like Sclera at ALL, “prioritize your eyes as much as your ears.” What are the defining qualities of this visual? Again, crudely put, there’s a focus on 3D, technic computer art with the nonhuman, otherworldly iconographies and a future-feeling visual language, which can be connected to an interest in video games and developments of technological capabilities.

2017 again. Together with I: project space, an independent non-profit space in Beijing, and Shanghai and Zurich-based DJ and creator Asian Eyez, we set up the Nightlife Residency. Now in its fourth year, the project aimed to operate explicitly in the intersection between contemporary art and electronic music/club culture, inviting a visual artist and/or musician for a two-month residency in Beijing to work on projects related to this field. We felt that a fresh club scene, with a distinctly audio-visual raison d’être, was now growing enough to warrant focusing on, and not in just Shanghai and Shenzhen but also in other spots across the world.

I don’t want to affix labels onto things here but what I posit we now see, not dissimilar from Simon Reynolds’ Conceptronica5For Reynolds, Conceptronica “isn’t a genre as such” but a “mode of artistic operation” which “offer a way for artists to compete in an attention economy”; characterized by “a warped-mirror relationship with contemporary dance styles” and a desire for a Gesamtkunstwerk world-building foregrounding the audio and the visual equally, as well as an “apocalyptic theatricality” and a “sense of drama and expressionistic excess hovering in an undecipherable zone between euphoria and dysphoria”. Simon Reynolds, ‘The Rise of Conceptronica: Why so much electronic music this decade felt like it belonged in a museum instead of a club’, Pitchfork, 10/2019, link., is this Chinese scene drawing on a decentralized and ahistorical blueprint for music that allows for the integration of vastly different styles and sounds from across the world, in a way that previous genres, tied more to individual cities and histories, did not allow for, making it perhaps more appealing to China-based producers tired of overshadowing European and American narratives in electronic music. Fixing a screen in the middle of the club performs a similar disavowal of historical precedents. One last mention of Conceptronica with a segue via the subtitle of Reynolds’ essay: “Why so much electronic music this decade felt like it belonged in a museum instead of a club.” A migration that mirrors aspects of this Chinese club ecosystem and also my own developing experiences in the scene.

By late-2018 I was working at M Woods Museum in Beijing, we wanted to open a nightclub and multidisciplinary space, named guī, which focused on this crossing of contemporary art and club culture. I managed the project to open guī in the basement of the new M Woods Hutong museum. We were specifically influenced by the increasing visuality of Chinese club culture and wanted to create a haven for this. Moreover, we saw audio-visual initiatives like Tate Lates at Tate Modern and Concrete Lates at the Hayward Gallery as justifications for our sense that this new kind of audio-visual club scene was worth pursuing in the museum context. Ultimately, what makes this closely-associated-to-contemporary-art club ecosystem so ripe for co-option by museums and galleries is precisely floating in the same ether as contemporary art. Therefore, and somewhat ironically despite many of the artists operating in this audio-visual sphere being led by a desire to make art outside of commercially led institutional contemporary art, many museums and galleries have been quick to open their doors to this scene.

A characteristic example of this burgeoning relationship was Trance, a 2019 exhibition at M Woods Museum in Beijing’s 798, in which artist Chen Tianzhuo took over the entire museum space for two days of 12-hour durational performances. Working with a team of performers, a new world was built within the space of the museum and while this decadent theatrical backdrop was left up in the months following the two-day performance, it was the intense live show that was key. Musicians, including City, Dis Fig, and Ylva Falk, produced music with synthesizers, drums, and vocals, culminating each day in a no-holds-barred hour-long rave. Off to one side of this central rave hall through a room with tens of posters from past club nights put on by Tianzhuo’s party collective Asian Dope Boys, was a dark room with stacks of speakers where the Japanese DJ Yousuke Yukimatsu played for the majority of the 12-hour performance. In many ways, the exhibition was the culmination of Tianzhuo’s explicit desire to operate simultaneously in the worlds of contemporary art and underground nightclubs. Trance demonstrates how the visual turn in this club scene has made it, for better or for worse, pre-packaged fodder for use in the contemporary art context. While the scene shows some resilience to hollow co-option by contemporary art institutions, an admirable resistance that lays with the individual and holistic creative strength and self-belief of the key players, I believe that select future cooperation can lead to exciting mutually advantageous future developments.

Tom Mouna is a writer, DJ and promoter based in Beijing and London. He has a background in the History of Art, studying for his BA and MA at the Courtauld Institute of Art. He has written for publications including Frieze, Kaleidoscope, Art Review, LEAP, zweikommasieben, aqnb, and is the Beijing Desk Editor at ArtAsiaPacific and previously the Art Editor at TimeOut Beijing. He has worked in curatorial roles at Red Gate Gallery and Red Brick Art Museum, both in Beijing, and currently manages guī, is 1/4 of the Nightlife Residency and 1/3 of the Beijing-based electronic music label DCYY.