it is beautiful to see

the world ending

in ways that are filled with agency

and find each other in the streets

rather than alone and afraid of touch.

another end of the world is possible

to make way for another …1Ripley Soprano, Materials (Wonder Press: New York, 2020).

—Ripley Soprano

The body has taken center stage in 2020. Like a rolling fog, COVID-19 descended upon the city of Wuhan in the first few months of the year, swiftly spreading and quietly infecting the bodies of hundreds and then thousands. Invisible to the naked eye this novel coronavirus transformed human behavior almost overnight — rearranging social patterns and causing us to question our own somatic vulnerability. Where many of us once took our bodies for granted, COVID-19 has revealed the privilege of corporeality. Within a few short months, nearly every country in the world had been affected, and as individuals, communities, and governments were forced to grapple with a biological crisis like no other experienced in this lifetime, new policies emerged that revealed not only the human body generally under attack, but particular groups of bodies as especially vulnerable due to biopolitical governmental regulation.

In May, five months into the pandemic, the body resurfaced in public discourse in a very different manner. As disparate communities found themselves in various degrees of lockdown, footage of the murder of a Black civilian named George Floyd by a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota surfaced and then diffused into the digital ether. As questionable governmental policies such as “herd immunity” emerged, favouring the economy over human life and disproportionately affecting Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) people, Floyd’s murder refocused public attention on somatic vulnerability, in particular with regards to Black bodies in the face of systemic racism, police brutality, and failing social systems. To date Floyd’s murder has sparked Black Lives Matters protests in nearly 10,000 cities across the globe. And as storms of masked protestors exploded onto the streets, I was reminded of “Sick Woman Theory,” an essay by Korean-American writer, artist, musician, and astrologer, Johanna Hedva, that reflects on the BLM protests in Los Angeles following the police killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner in 2014. In their text, Hedva challenges German political philosopher Hannah Arendt’s definition of political action as necessarily taking place in public, posing the question: “How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can’t get out of bed?” 2Johanna Hedva, “Sick Woman Theory,” Mask Magazine, The Not Again Issue (No 24), January 2016, http://www.maskmagazine.com/not-again/struggle/sick-woman-theory. Saddled with multiple and chronic illnesses including endometriosis — a painful disorder in which tissue similar to the lining of the womb grows and bleeds cyclically in other places of the body — Hedva’s own corporeality provides them with an intimate understanding of the precariousness of embodied life. But only this year, at the apex of two biological crises, has somatic vulnerability permeated the public consciousness. Only this year have we been forced en masse to grapple with our bodies and to consider how we relate, in our fleshiness, to each other and to the world.

If you can’t see it, is it really there?

If I can’t see you, do you exist, and do I exist to you?

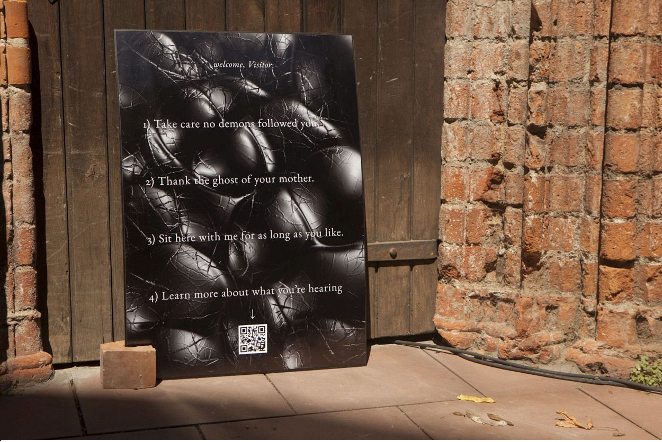

Situated in the mystical Klosterruine, a cultural space and the remains of a 13th-century Franciscan monastery in Berlin, Johanna Hedva’s exhibition God is an Asphyxiating Black Sauce meditates on absence through the concept of accessibility. Structured fundamentally against the ableist notion that art is best experienced in person, Hedva’s exhibition took place not only physically at the monastery — which as an architectural structure teeters on the edge of the binaries of life and death, inside and outside — but also virtually at http://godsauce.black/. In the artist’s own words, the shape-shifting-ness of the pieces in the show are the blood and spit and bone of the exhibition3Emily Watlington, “The Artist Who Writes In Their Sleep”, Artnews, July 2020, https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/johanna-hedva-writes-in-their-sleep-1202695388/. , prompting us to consider if we must do away with traditional understandings of medium and form if art is to adequately address the issue of accessibility. Though the events of this year have pushed the general public further towards recognition of the privilege of embodied life, Hedva’s practice has always been rooted in the assertion that physical absence should in no way determine one’s appearance or access to any realm, be it artistic or political. Sitting at the nexus of audial, visual, and spiritual experience, Hedva’s exhibition attends to all the bodies of their audience, no matter where they are located in the world or whether they are physically able to visit the show.

The central work in God is an Asphyxiating Black Sauce is a sound piece titled “Playlist to a Void.” The 38 tracks on the playlist are comprised of poems and essays read aloud by Hedva, songs from their 2019 EP The Sun and the Moon and forthcoming LP Black Moon Lilith in Pisces in the 4th House, as well as pieces by composers and collaborators Gabie Strong, Pauline Lay, William Fowler Collins, Geneva Skeen, and Anja Kanngiesser. Comingling with Hedva’s spoken tracks, the musical compositions are a net of disjointed vocals, electric guitar, piano, trumpet, stringed instruments, and heavily edited samples, woven together through scratchy modulations and ghosty reverb. Hedva’s own voice, which they employ with emotional precision, has a distinct muted quality that is immediately discernible. On the first track of the playlist, titled “How to Write,” their vocal world-weariness coupled with languid pronunciation of words such as ‘o-le-a-ginous’ (rich in, covered with, or producing oil; oily) beckons listeners into a trancelike state. French philosopher, mystic, and political activist Simone Weil also haunts the playlist, where Hedva has fractured, modulated, and overlaid her voice on the seventh track, titled “Beauty.” Not only does the multidimensional format of God is an Asphyxiating Black Sauce attend to issues of absence and somatic accessibility on a structural level, but Hedva’s essays, poems, and songs lead us towards an inner sanctum in which they ask, is absence ever really empty, and does absence ever truly exist? 4Watlington, “The Artist Who Writes In Their Sleep”.

Hedva’s writing attends to these questions through a series of recurring linguistic tropes. Running at only 28 seconds track 22 on the playlist presents a microcosmic snapshot of these motifs:

The moon, magic, my mother: for how to disappear

completely and then return, I’ve had the best teachers

This sentence, albeit concise, performs in a multiplicity of ways. The counterintuitive structure and gentle use of punctuation creates a rhythm that toys with the listener (or reader), creating space in pause and a distinct, almost physical feeling of push and pull. The sentence activates the past as a force to generate nostalgia and, perhaps most powerfully, the moon, magic, and Hedva’s mother are lassoed together in their shared slipperiness. As symbolic constants in their writing, these three entities are the ultimate signifiers of ebb and flow, waxing and waning, disappearance, and reappearance — of something that is at once mercurial and constant. The effect is one of emotional and psychic conjuring, but also emptying. Hedva explores absence through the creation of literal and figurative negative space.

The varied work that appears on “Playlist to a Void” is as imaginative as it is erotic, typifying Hedva’s linguistic power. There are no tales of sexual exploit, no dildos or mentions of engorged body parts, but, after Audre Lorde, their work is a resource existing on a deeply “female” and spiritual plane. Their writing is a feeling. It is the assertion of life-force, creative energy, and knowledge. It is not only the reclaiming of language but also of different artistic mediums, including the virtual. Extending from the depths of their corporeal experience the erotic in Hedva’s work helps to create a dimension for engagement that is generous and inclusive.

In the physical exhibition in Berlin “Playlist to a Void” played in loop over speakers in the altar section of the Klosterruine. Standing between the only two walls of the ruin that still remain intact, encircled by towering, glassless arched windows and open sky overhead, I can imagine the audio-visual emptiness that visitors would have experienced. I can imagine the excitement, the reverence, and the yearning that is induced by something that is unseeable but that is assuredly present. More than a month after the physical exhibition has been dismantled I sit in my east London flat experiencing God is an Asphyxiating Black Sauce for the first time through a laptop and headphones. I was not in Berlin physically to see the exhibition, nor have I been on a plane since December 2019, but Hedva’s ongoing consideration of accessibility allows me to experience their show virtually.

The online version of the exhibition is a simple website through which visitors can experience the pieces in the show. The bottom half of the page contains an audio player with all 38 tracks from “Playlist to a Void,” above which there is an option to display the text in full for Hedva’s essays, poems, and songs, along with the compositions by their collaborators. Sitting in London on my computer, listening to the playlist while simultaneously being able to read alongside their voices, I am not only completely immersed in the experience, but I am grateful for my own able-bodiedness and understand through this, the importance of accessibility. As someone who was not able to physically attend the exhibition, I feel considered, and cared for. I navigate to a tab on the website that reads “Accessibility” and finds a meticulous description of the site and location of Klosterruine: “The closest subway station Klosterstrasse is approximately 50 meters from the site, however, the station is not wheelchair accessible… Once inside, there are four levels that are connected by stairs…The ruin has no roof and, when it rains, the steps and the floor can be slippery.” Presumably written by Hedva, this parsing of the physical components of the Klosterruine goes far beyond the usual information provided by museums and galleries to their visitors. If the embodiment is a privilege, Hedva’s approach to exhibition-making is the ultimate acknowledgment. Though I am uncertain how long the online version of the show will remain accessible, interacting with it has allowed me to glean contemporary art theory and practice operating in a manner and register that attends to some of the most pressing social, political, and biological issues of the day. God is an Asphyxiating Black Sauce is Hedva’s artistic expression of their political and linguistic concerns with the body, and with their care for embodied life.

So in 2020, can we say that the body is finally beginning to be understood, at a global level, in its vulnerability? Have the Black Lives Matters protests this year effectively articulated the ongoing somatic precarity experienced specifically by Black communities? And has the COVID-19 pandemic truly instigated a transformation in the way we understand the social and political issues surrounding embodied life? What can be said with certainty about 2020 is that work and play is increasingly located virtually, and that we must therefore become not only acquainted but intimate with the notion of absence. If the true nature of life online remains out of sight and therefore unscrutinized5Geert Lovink, “What is the Social in Social Media?” on The Internet Does Not Exist (Sternberg Press: Berlin, 2015), 167. , then perhaps we are more familiar with physical nonappearance than we readily know. And if corporeality is what defines human life — bodily joy, desire, sensual experience — and we are able to experience these tones and textures through the work of artists such as Johanna Hedva, then it must be possible, and perhaps even certain, that we can come together in absence, in nothingness, in 2020 and beyond.

Kate Wong is a Chinese-Canadian writer and curator living in London, UK. Interested in discursive approaches to art and knowledge production she is the founder of low theory (https://linktr.ee/lowtheory), a bi-annual digital journal and curatorial project that considers alternative modes of thinking, and that focuses on interdependency as decolonial praxis. Recent projects have been driven by a continued interest in political philosophy, and have focused on radical materialism, the feminist imagination, and on embodied virtuality. Wong’s writing on contemporary art and culture has appeared in TANK Magazine, Yishu Journal, Frieze Magazine, and Another Gaze Journal, among others, and she is an Associate Lecturer at the University of the Underground’s New Politics and Afrofuturism programme (http://universityoftheunderground.org/kate-wong).