One night a few months ago, my conversation with a friend drifted from works we had seen recently (some by artists in Hong Kong, others from a group show on view at Asia Society) to the violent incidents — bombings, robberies, murders, disputes, etc. — that saturated Hong Kong newspapers and magazines throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. The articles from that era tended to be short in length and ice cold in tone. We took turns speculating as to why coverage had been so scant when the violence was so rampant. At first glance, such sensational social matters would appear worthy of lengthy coverage and dramatic emotional investment, especially in Hong Kong’s business-oriented society. As I pondered those events and the emotions they evoked, I was reminded of the magazine Bosom Friend, which was something of a household name in mainland China throughout the ‘90s and 2000s. When I was in elementary school and junior high, there were always a few copies in the pile of family and women’s magazines on my mother’s nightstand. The content was a preposterous yet somehow fitting hodgepodge, conveying tales of family warmth alongside sermons on social ills and the dangers of lust. What kept the reader perennially hooked was the mixture of strange passion and cloying sentimentalism in the articles — not unlike the emotional undertones of viral videos on today’s social platforms, like TikTok and Kuaishou, with their hollow, irresistible attraction.

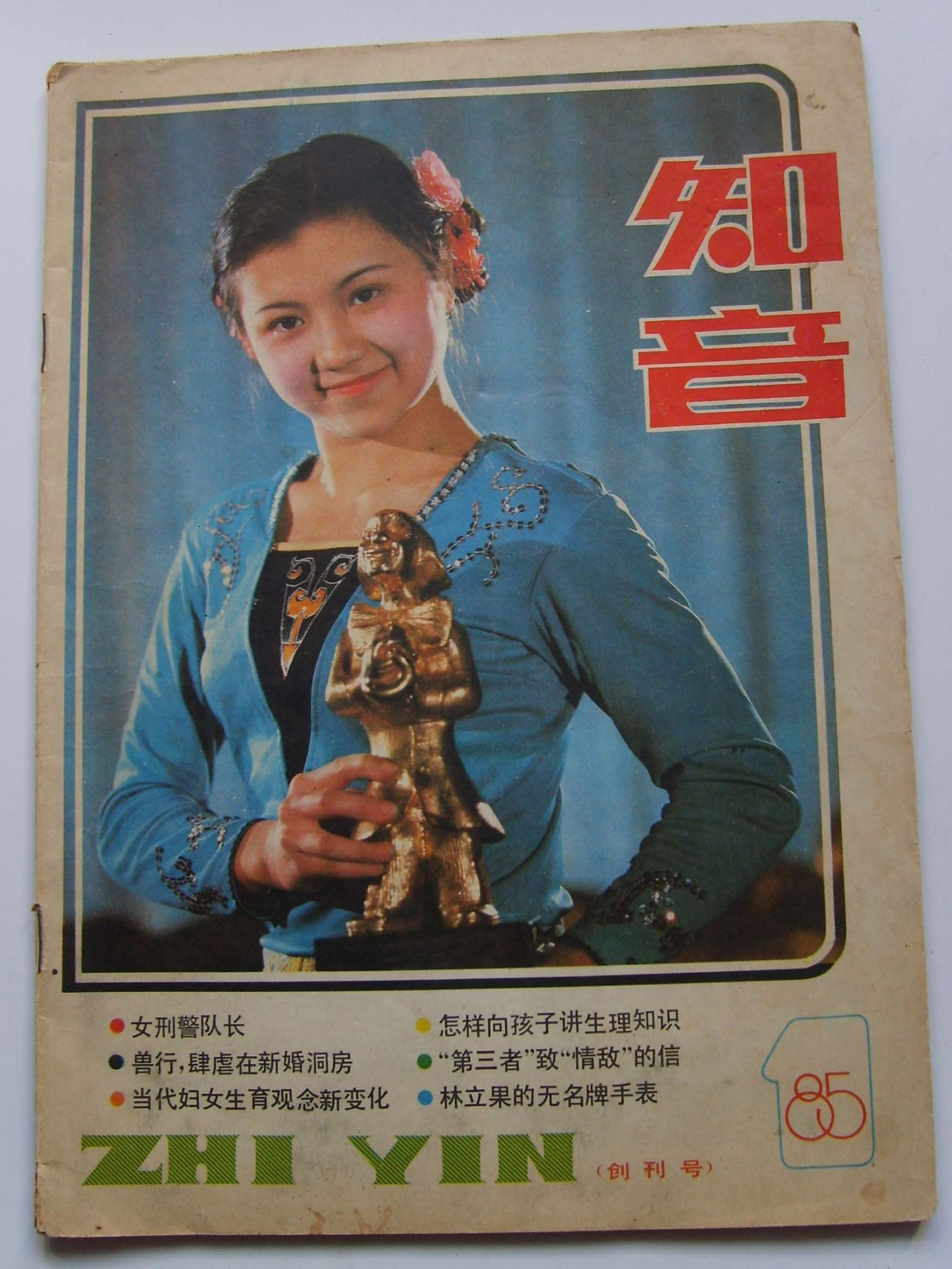

Prompted by nostalgia, I went online and ordered the inaugural issue of Bosom Friend published in 1985, intending to research the historical trajectory of what was once the women’s magazine with the greatest circulation in China. In 1980, amid various political and economic reforms, China implemented the New Marriage Law, a measure taken as part of its call for the family to assume the status of the basic social and emotional unit in the post-collectivist era. Shortly after, women’s federations across China started launching women’s magazines, one after another, as a way to revive discussion about women and the family. Bosom Friend was founded by the Hubei Women’s Federation, and its title is taken from a line of poetry about the classical friendship of Bo Ya and Zi Qi, who famously met in Hanyang, Hubei: “Meeting the bosom friend amid the melody of high mountains and flowing water.”

Continuing the metaphor of melody and bosom friend1This metaphor comes from the traditional Chinese story “Boya Cuts the Strings (Bo Ya Jue Xian)”, where Boya cuts his string and stops playing music after the death of his bosom friend Zhong Ziqi. , the inaugural issue published a statement in its closing pages that described its goal as touching the heartstrings of women readers, linking them heart to heart. Compared with the impassioned writing that later filled the pages of the magazine, the inaugural issue’s prose was in a subtler register, its articles were mostly shorter, and each column had a clearer theme. Underlying this compilation of articles, one can still sense a stream of latent, wavering forces that perhaps reveals the undulating emotions beneath official history, while concurrently anticipating some of our contemporary sentiments:

Contemporary Women, the opening column, addresses the new values of professional women, whose focus had been shifted from reproduction to the respect and love of a career;2“Female Police Captain,” p4; “New Changes in Contemporary Women's Concept of Reproduction,” P7 two stories in the Before and After Marriage column warn married women not to be blinded by the “new women’s call for courage and independence,” and not to give up on the hard-won love of their families due to the husband’s extramarital affairs.

The Young Women Must Not Be Deceived column features two stories about domestic violence. One is about the murder of Xiu fang, a simple village woman, by her husband Chang Ping, a doctor who fell for a mistress;3“The Mystery of a Wife’s Sudden Death,” P8 the other is about the brutal rape of village girl Jiang by her husband, through a mercenary marriage, and his accomplices.4“Beastly Behaviors in the Bridal Chamber,” P10

Two other fictions in the Before and After Marriage column offer opposing guides to love side by side: After entering a relationship with Zhu Zhengguo via family introduction, Li Zhenru stands firm with her morals to reject Zhu’s material temptations and physical advances. As the two eventually break up, Li has managed the praiseworthy task of “[safeguarding] her virtue, with which she will most certainly find true love in the end.”5“She Used Rationality to Purify Love,” P16 “My Pride Pushed Away My Prince,”6P17 however, presents a letter from a woman to her younger sister, in which she shares her remorse about a relationship that ended because of her pride, and advises her sister that there is no place for pride in matters of the heart: “Your sister has already swallowed the ‘bitter fruit.’ You must not repeat the same mistakes!”

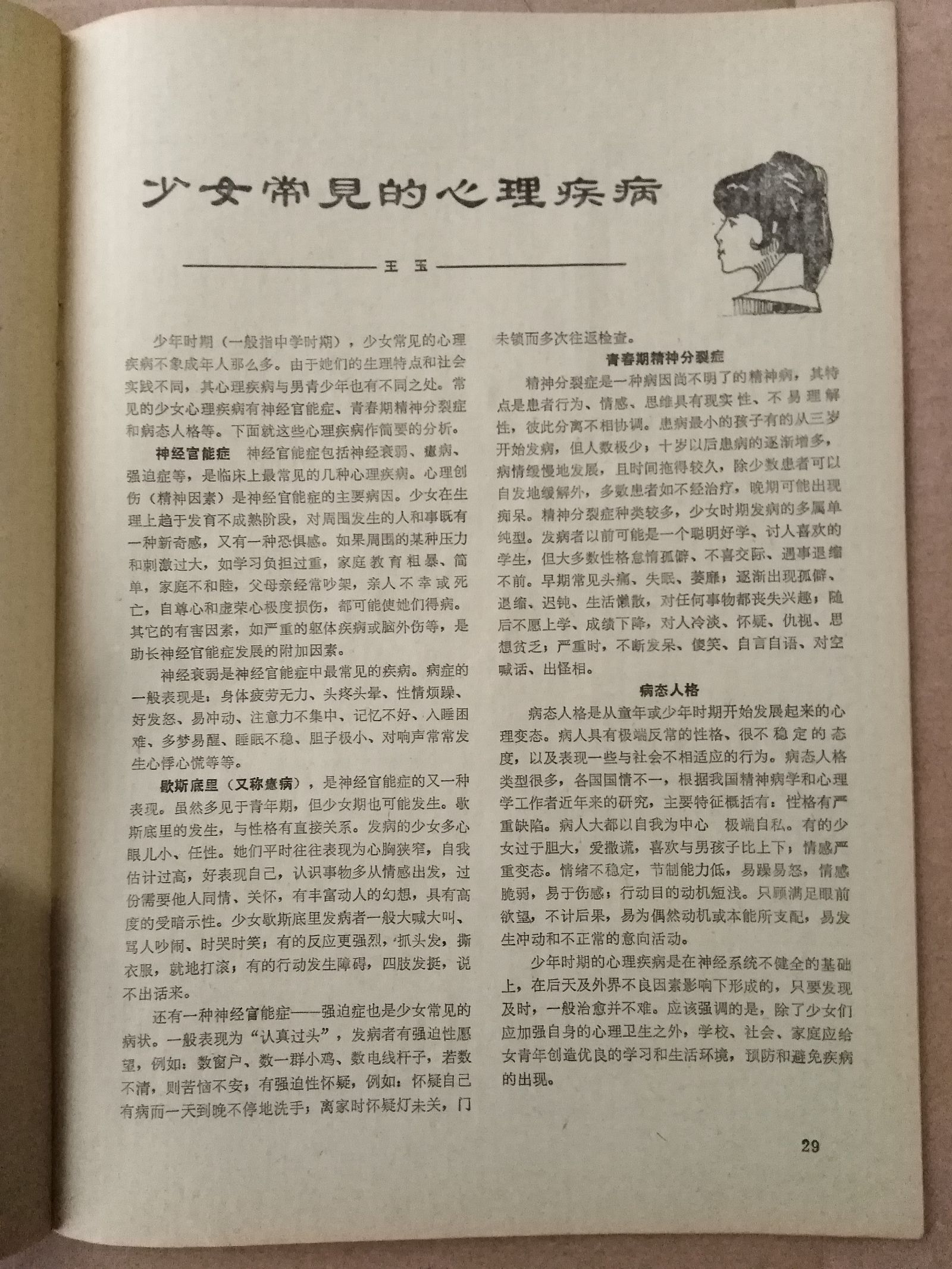

Through these parables—in the painful choices between continuing or giving up on love, between remaining reticent and taking command, and between betrayal and forgiveness—one can start to trace the contours of a subservient female body being relentlessly torn apart by myriad forces, such as the moral code of love and fidelity, the modern ethos of freedom and emancipation, and Confucian ideas about family and compromise. Towards the end of the issue, a translated popular science article conveniently introduces “common mental illnesses among young girls” 7P29of the time, which include neurosis, hysteria, adolescent schizophrenia, and pathological personality. By placing this article after the previous ones, which are meticulously arranged to augment a sense of schism, the inaugural issue normalizes these female “illnesses,” while also drawing a causal link between the many forms of labor and virtue ascribed to women (such as diligence, self-reliance, fidelity, and poise) and their pathologies.

The historical ties between “mental illness,” women, and love became deeply entangled as early as during the Chinese enlightenment movement of the 1920s. Much of the literature produced by women at the time, such as Ding Ling’s early novels, revolved around the “neurotic” nature of women. As the New Culture Movement strove to overthrow feudalism and called for a radical break with the traditional family, women, once relegated to a subservient role, took on the liberated subjectivity of the New Woman (xin nvxing) to become spokespeople for the “free pursuit of love.” Desire and emotions now became their defining characteristics, while drawing the limits of their self-exploration at the same time. This explains why the New Women in Ding Ling’s novels always had English names, were deemed flighty and overemotional, indulged in lust, and suffered from inexplicable pains; perhaps they can be read as the prototypical Chinese “Mary Sue”8The fictional, idealized female protagonist in much of contemporary popular literature: even as they were inadvertently pushed onto society’s central stage, and applauded for it, they continued to struggle between fantasy and forgetfulness, political zeal and uncertainty regarding the self. Towards the end of the 20th century, Ding Ling finally found an anchor for the personality of her “neurotic” female protagonists in her revolutionary pursuits and started her “revolution + love” writing project. However, after half a century of revolution and political upheavals, female subjects — “liberated” once again by China’s reform policies — entered the modern family, where “mental illnesses” lay in ambush as Bosom Friend stroked their heartstrings. The female protagonists of Ding’s early work, who embraced love and desire but did not know what they wanted, found new life in the works of women writers such as Anni Baobei, Wei Hui, and Mian Mian in the 1990s and 2000s. As these writers withdrew to live in seclusion or turned to religious and spiritual pursuits, one after another, did they not also undergo a kind of “liberation” or “discipline” parallel to Ding Ling’s? With the countless attempts to emancipate human nature and revolutionize emotions, stories of emotions swelled with myriad political positions and intentions, at once recognizable yet strikingly different Bildungsromane. Women and love are, as succinctly captured in Lata Mani’s observation on discourses on women and tradition in colonial India, “neither subjects nor objects, but rather the ground of the discourse.”9Lata Mani, “Contentious Traditions: The Debates on Sati in Colonial India”, 1989

In the early 1920s, scandal fiction met with much fanfare and was commonly serialized in Shanghai newspapers and magazines. One such narrative, titled Ten Sisters, told the “classic” story of a young girl’s fall in the metropolis: Ye Tihong, a student, meets the handsome swindler Cai Bodang in Shanghai’s notoriously messy night garden and falls in love; soon, prey to a scheme organized by her own sister, she breaks off ties with her wealthy family, cancels her initial engagement, and, after being defrauded of her possessions, eventually commits suicide.10Hai Shang Shu Shi Sheng, “Ten Sisters,” 1918 In the essay “Revisiting Scandal,” Zhou Zuoren examines depictions of social and moral chaos in scandal literature; observing its tendency to cater to the psychology of modern Chinese society in terms of moral views and philosophy of life, he argues that the history of scandal literature is a “valid and fitting archive for the study of psychological perversions in the social conditions of the Chinese nation.”

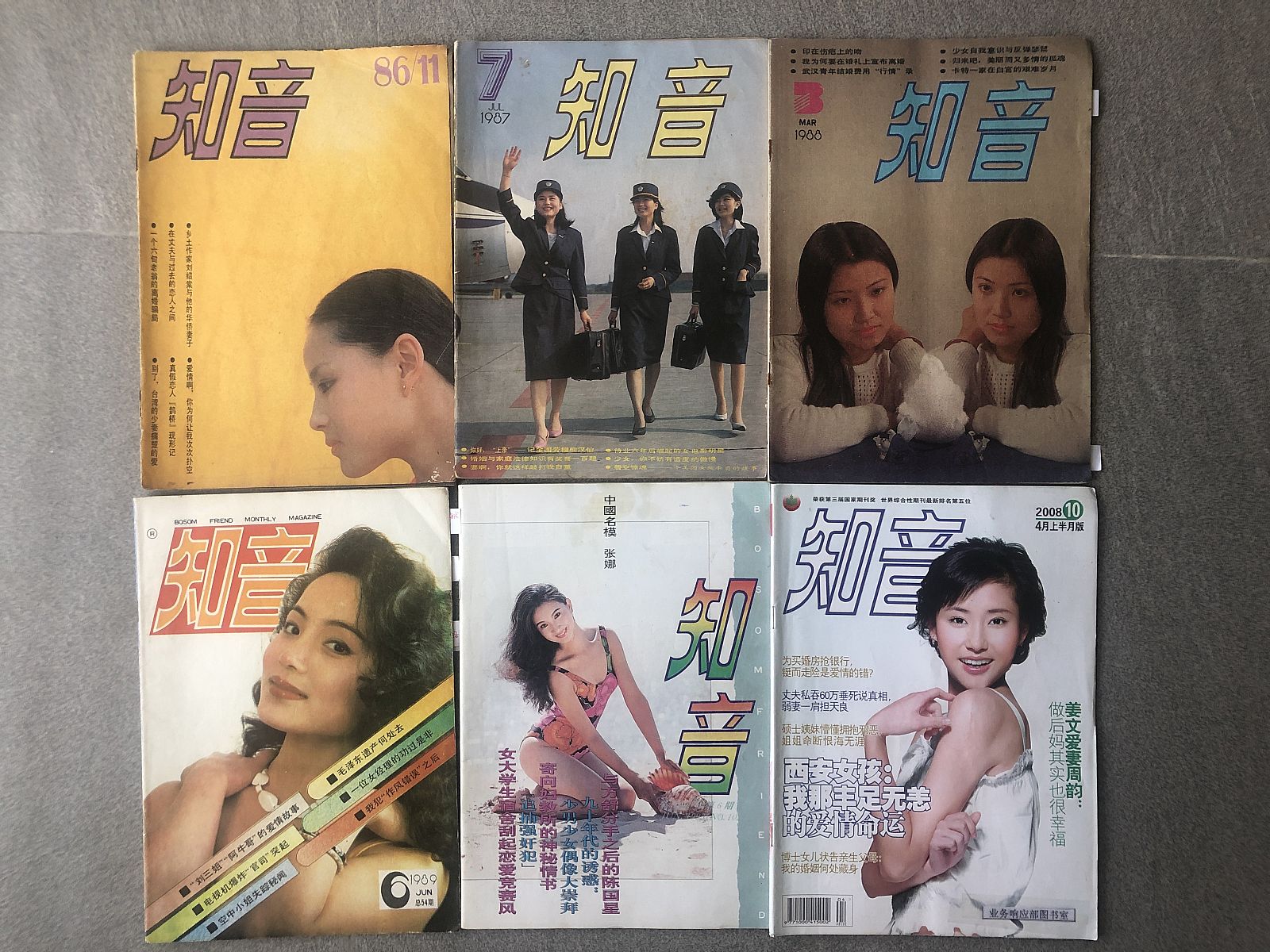

Over half a century later, the same sort of scandal literature that used to be all over the tabloids was resurrected in Bosom Friend, which “for many years steadily ranked first in domestic circulation and fifth globally,” and situated the site and trajectory of the “emotional conditions of Chinese society” from the 1980s through the 2000s in a landscape outlined by contemporary emotions and love. An article titled “The Mysterious Disappearance of a Stewardess” in a 1989 issue told a story much like Ten Sisters: Fang Jing, a pretty stewardess seduced by vanity, breaks up with her boyfriend, falls in love with a rich businessman from Taiwan, and plans to run away to Australia with him to get married. The civil aviation administration intervenes, and Fang is captured by the police in Guangzhou, only to learn that the businessman is already married. And so she “bursts into tears as she murmurs: ‘It’s over, it’s all over…’” 11“The Mysterious Disappearance of a Stewardess,” Bosom Friends, Issue 6 1989

While Bosom Friend has largely been disregarded as a product of a bygone era, and is despised by mainstream culture for representing the taste of the lower ranks, its unique verve still lingers to this day. Its signature sensationalist column titles have been picked up by many popular online tabloids and media platforms, while its soul-stirring sentimentality has, to a certain extent, set the tone for the storytelling of private and public affairs in Chinese society. Perhaps the tales of family and emotion that once so captivated us, with their many ups and downs, are still reverberating in our homes and streets, weaving ties between private and public in the language of emotions and politics. After all, (women’s) bosom friends and (social) unity have long been a harmonious pair — in the spaces we inhabit, emotions and power always complement one another, just like high mountains and flowing water.

Translated from the Chinese by Alvin Li.

Qu Chang is a Hong Kong and Shenzhen-based curator and writer contributing to journals such as Artforum, Ocula, and Yishu. Qu is currently a student of the Cultural Studies Ph.D. program at Lingnan University, Hong Kong. Prior to that, she worked as Curator at Para Site. Her recent curatorial projects include Lo Lai Lai Natalie: The Days before the Silent Spring (2020), Sea Breeze (2019, Jogja Biennale, co-curated with Cosmin Costinas), Café do Brasil (2019, Para Site), Doreen Chan: Hard Cream (2019, HB Station), Crush (2018, Para Site), among others.

Alvin Li is a writer, a contributing editor for frieze, and Adjunct Curator, Greater China, Supported by the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation, at Tate. He lives and works in Shanghai.