Before I learned about Boris Groys’s analogy of art criticism as a binary system of ones and zeros — the author’s endorsement or disdain is hardly relevant, and what truly matters is whether the artist is mentioned, published, illustrated, featured on the front page 1Lütticken, Sven. “A Tale of Two Criticisms,” in Judgment and Contemporary Art Criticism. Ed. Jeff Khonsary & Melanie O’Brian (Vancouver: Artspeak / Fillip Editions, 2010). p. 51. Originally from “Who Do You Think You’re Talking to? Boris Groys in Conversation with Brian Dillon,” frieze no. 121 (March 2009), p. 126-31. — I had actually reached a similar conclusion from my own experience writing reviews for art media: Writing itself is acknowledgment, and nothing is crueler than not writing.

To choose not to write is one of the few liberties that I enjoy. Most of the time, I endeavor to endorse and support artists through my writing. That’s why I once held the principle of producing only positive reviews. In retrospect, my fragmented writings are mostly genuine, and they surely qualify as good promotional-kit inserts. One could easily pick out some memorable sentences or helpful footnotes from therein; they are serviceable fuel for this industry.

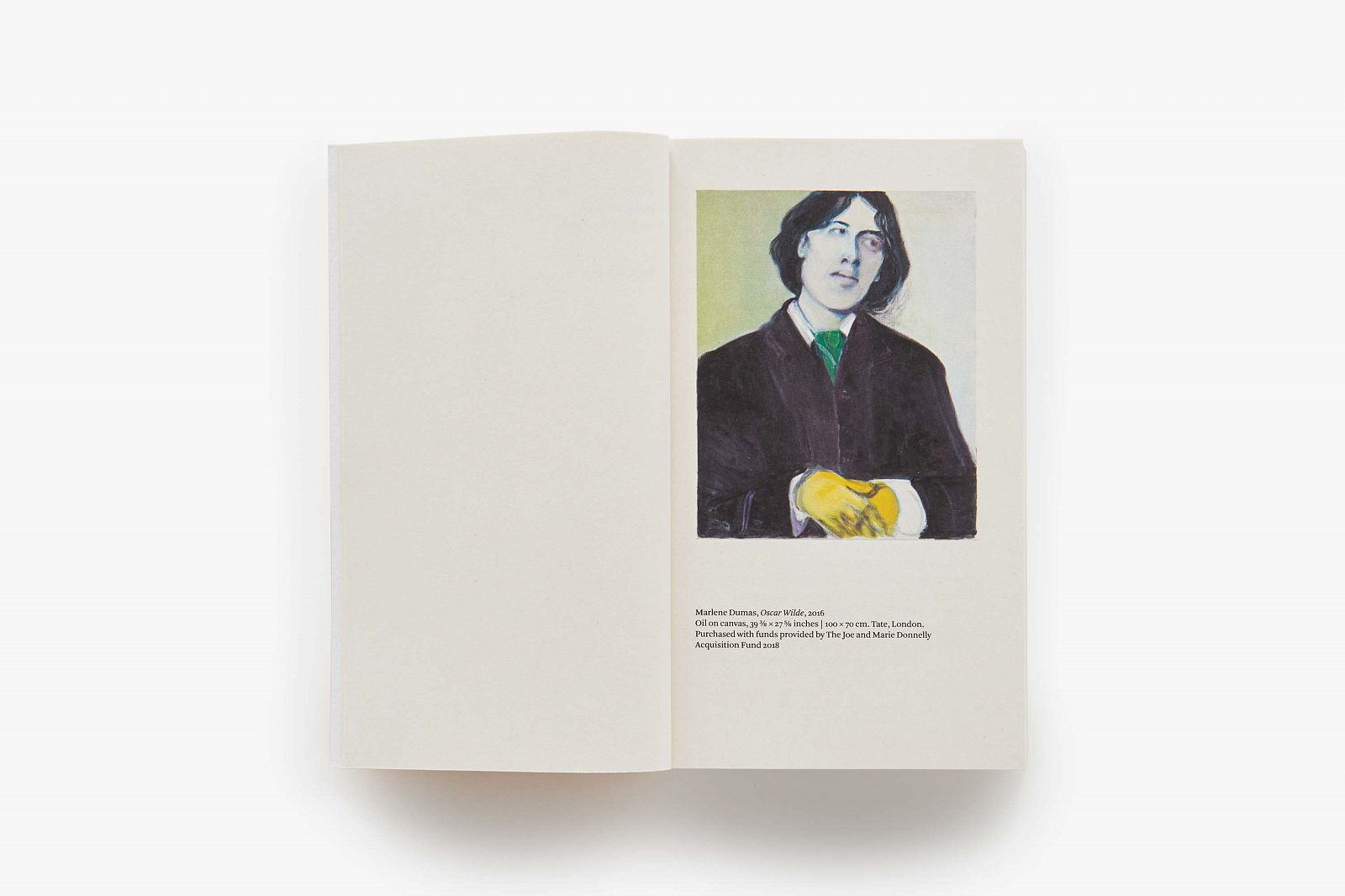

I haven’t written seriously for a long time. Towards the end of February, in a rare gesture, I wrote a harsh critique to express my dissatisfaction with the Rem Koolhaas show at the Guggenheim (which was published on Leap). And then I fell into a hiatus. While it was true that there were no new exhibitions to see, I also had no motivation to write. The freedom of not writing came too suddenly, and I found myself luxuriating in other projects: translation, editing, exploring social media, and art publishing. In my spare time, I read Oscar Wilde’s dialogue-based essay “The Critic as Artist” twice. The jocular subtitle of its first scene was surprisingly appropriate: “With Some Remarks on the Importance of Doing Nothing."

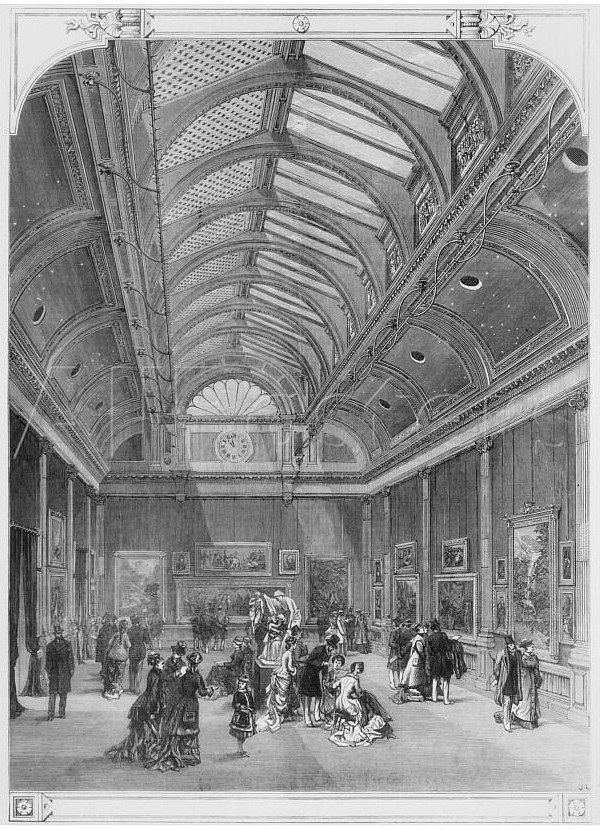

Wilde’s first published piece of journalism was actually a review of the Grosvenor Gallery’s opening exhibition in 1877.2Please see Link. He even wrote another article on the same gallery’s annual exhibition two years later, further corroborating that his status as critic was not just a fluke, and demonstrating that “The Critic as Artist” was thus self-critical. What’s more, the essay was originally published in the literary magazine Nineteenth Century under the title “The True Function and Value of Criticism”; the snappy title we know today came later, when it was published in his essay collection Intentions. Apparently, Wilde was not satisfied with writing art reviews, nor did he aspire to realize the value of criticism. Still, he commended the ethos and creativity of criticism nonetheless. Through his character Gilbert, Wilde asserts: “Criticism is itself an art … a creation within a creation,” and that “the highest Criticism, being the purest form of personal impression, is in its way more creative than creation.”

I find the last quote compelling. “The purest form of personal impression” points to the autobiographical potential of criticism. In other words, if we compiled a particular critic’s works, we could outline a personal history of ideas, and it would take the form of a forthright summary, without the distractions of branching narratives. Case in point: T.S. Eliot’s widely-celebrated To Criticize The Critic, wherein he reviews his past works of criticism and candidly admits: “There are, to be sure, statements with which I no longer agree”; “There are errors of judgment, and, what I regret more, there are errors of tone”; yet, “I continue to identify myself with the author.”3 Eliot, T.S. “To Criticize the Critic,” in To Criticize the Critic and Other Writings (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1965), p.14.

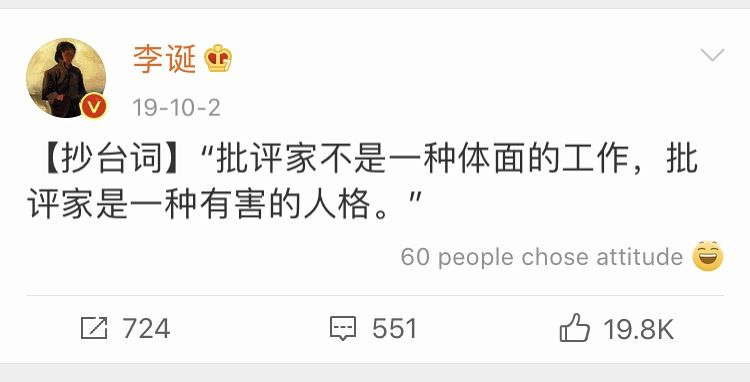

Wilde put criticism on a pedestal through three layers of progression. Though his tone may be condescending, his fundamental argument offers an effective counterpoint to the perspectives of people such as Li Dan, one of the most famous Chinese stand-up comedians, who declared on Weibo: “Being a critic is not a presentable profession; It is more of a pernicious persona.” But I’d come across as conceited to repeat them to myself. Besides, we don’t need to resort to criticism to plot a personal history of ideas nowadays, as such a feat is easily achievable through posting on social media.

For me, “The Critic as Artist” was cathartic to read. Fictional characters Gilbert and Ernest take turns to argue, refute, dispute, and interrogate. Gilbert, who carries Wilde’s subjectivities, has the slight upper hand as he eloquently advocates his theories through lengthy speeches; Ernest teases out Gilbert’s ideas, guiding the conversation’s flow by asking one tough question after another. The back-and-forth between the two resembles an intense ping-pong match, tracing the trajectory of criticism through backhands and forehands. To illustrate:

E: “… in the best days of art there were no art-critics. … All subtle arts belonged to [artists] ... The Greeks had no art-critics.”

G: “… It would be more just to say that the Greeks were a nation of art-critics.”E: “[It] seems to me that most modern criticism is perfectly valueless.”

G: “So is most modern creative work also.”E: “[It] was more difficult to talk about a thing than to do it?”

G: “(after a pause). Yes ... When man acts he is a puppet. When he describes he is a poet.”E: “I would have said that personality would have been a disturbing element.”

G: “… as art springs from personality, so it is only to personality that it can be revealed.”

As the debate unfolds, Wilde provides us with a clear definition for the act of criticizing: “the critic is he who exhibits to us a work of art in a form different from that of the work itself.” “A different form” entails the introduction of new materials, implying that this act is at once critical and creative. Wilde furthered this definition in the prologue to The Picture of Dorian Gray: “The critic is he who can translate into another manner or a new material his impression of beautiful things.” This endeavor to “translate beauty” bridges criticism and creative work, and, consequently, “the critic” as perceived by Wilde could very well be an artist: “The actor is a critic of the drama”; “The singer or the player on lute and viol, is the critic of music”; “The etcher of a picture ... is, in his way, a critic of it.”

At this point, you may accuse me of mixing concepts. However, in the contemporary context — after more than a century of myriad isms — “translate … his impression of beautiful things” also seems to raise more questions than it answers: What beauty? What impression? So here’s my theory: On the one hand, following Wilde’s aestheticism, artists gradually began to view art-making itself as a criticism. As Jasper Johns once said, “Art is the best art criticism.” On the other hand, the critic’s task has been stripped down to that of “translating,” or even more reductively, of paraphrasing.

Therefore, the aforementioned binaries of one/zero or writing/not writing highlight the same dilemma in contemporary criticism. The voice of professional art critics writing for the art media can now be summed up in three words: “Look at this!” More often than not, the critics’ identities are blurred, their personalities absent, for there is no need for such individuality. They might as well be anonymous. Criticism has more or less become a mix of quotations from exhibition press releases and artist statements, and the role that the critic fulfills has become that of a sign-holder: “Car Washing. Turn Left at the Next Intersection.”

But even if the critic’s task has been deflated to that of paraphrasing, the capacity to criticize is still a privilege in many ways. To name a few: critics/paraphrasers are usually among the first to be invited to a vernissage, they can more easily correspond with artists, and their reviews are usually hailed as the mainstream media’s voice. To the public, “Look at this!” is often read as “Ain’t this great?” This association is a short-cut conclusion drawn from our fast-food culture that accelerates feedbacks to be the default positive ones so that they can be adapted as chips in various markets, but it also emerges from the onslaught of positive reviews produced by critics such as myself. I think a critic should first learn to acknowledge their privilege, then develop methodologies suitable for their own ideologies. For example, Roberta Smith believes that it is simply impossible for a critic to mingle with artists, and this has even become an issue of professional ethics for her. Since the ‘90s, she has ceased to write reviews on artists whom she was acquainted with or to visit studios before writing: “I felt that if I went to one artist’s studio, I’d have to go to all artists’ studios — it wouldn’t be fair.”4Earnest, Jarrett. “Roberta Smith,” in What it Means to Write About Art: Interviews with art critics (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2018). p. 463

I frequently caught my mind drifting as I read “The Critic as Artist.” As I read the section “With Some Remarks on the Importance of Discussing Everything,” in which Gilbert argues that art does not hurt people, I reminisced about an uncle. This distant relative of mine (who hails from Yunnan, I think) dwells among my hazy elementary school memories. He was a firm believer in UFOs and always carried a thick notebook with him. The notebook had a framed black hard cover. In it, you’d find cutouts of newspaper reports on UFO sightings and, next to them, his sprawling notes and drawings made with a blue ballpen. I recall adults giggling and mocking him as he flaunted the notebook, as though he were spouting pseudoscience. He surely didn’t mind, however, and continued to prattle on. Then, turning to me, he suddenly asked, “Do you believe in UFOs?”

I had no clue. His question far exceeded my childhood capacity to understand the world or make judgments. But this notebook captivated me nonetheless. Every sentence in the notebook appeared familiar despite my incomprehension, and every image enchanted me even though I found them all undecipherable. It was like a book from the sky, something categorically different from any textbook, folktale, or storybook that I had read. It was ancient and distant, but all the same animated with a fresh and novel aesthetic.

A conceptual aura surrounds the word “UFO.” Whether UFOs exist or not is besides the point. The mere utterance of the word conjures up the descriptions, discourses, imaginations, and reifications associated with it. Years later, many of the concepts on display in contemporary art exhibitions strike me in similar fashion. They make me feel at a loss, much like how I felt when I was confronted with my uncle’s question.

Evidently, when dealing with concepts and their resultant forms, criticism as paraphrasing is far from adequate. It has no power to capture the mixture of confusion, appreciation, skepticism, and affect that arises from the viewing experience. “Look at this!” is an authoritative command, but also the signal of an intellectual and expressive sloth. In response to such sloth, I’d like to distill Wilde’s “translate … his impression of beautiful things” into simpler terms: the [task of the] critic attempts to communicate an understanding of concepts. If criticism has an ideal form, it certainly wouldn’t resemble the crisp absoluteness of binaries. Instead, it would be muddy and obscure. It would dare to expose the viewer’s powerlessness, and it would render concepts as flesh and bone. I wish to seek liberty through such writing.

Translated from the Chinese by Kevin Wu.

Qianfan Gu is an art critic and writer based in New York. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, Artforum and Artforum China, LEAP, Flash Art, artnet News, The Art Newspaper China, Esquire China Magazine, Wallpaper China Magazine, Life Week, The Paper, and several others. She was shortlisted twice, in 2015 and 2016, by International Awards for Art Criticism (IAAC). In 2019, she received a Special Honorable Mention from the Incentive Award for Young Art Critics by the International Association of Art Critics (AICA). She is a co-editor of Heichi Magazine, also the co-founder and publisher of Gong Press.

Kevin Wu is a freelance writer, translator, curator, and artist living and working in New York. Kevin graduated from Columbia College in 2018 with a degree in art history and visual art. He is currently pursuing an MA degree in curatorial studies at the School of Visual Arts. In 2019, he served as curatorial assistant in the 5th Ural Biennial. His current research interests include hauntology, posthumanism, and sci-fi.