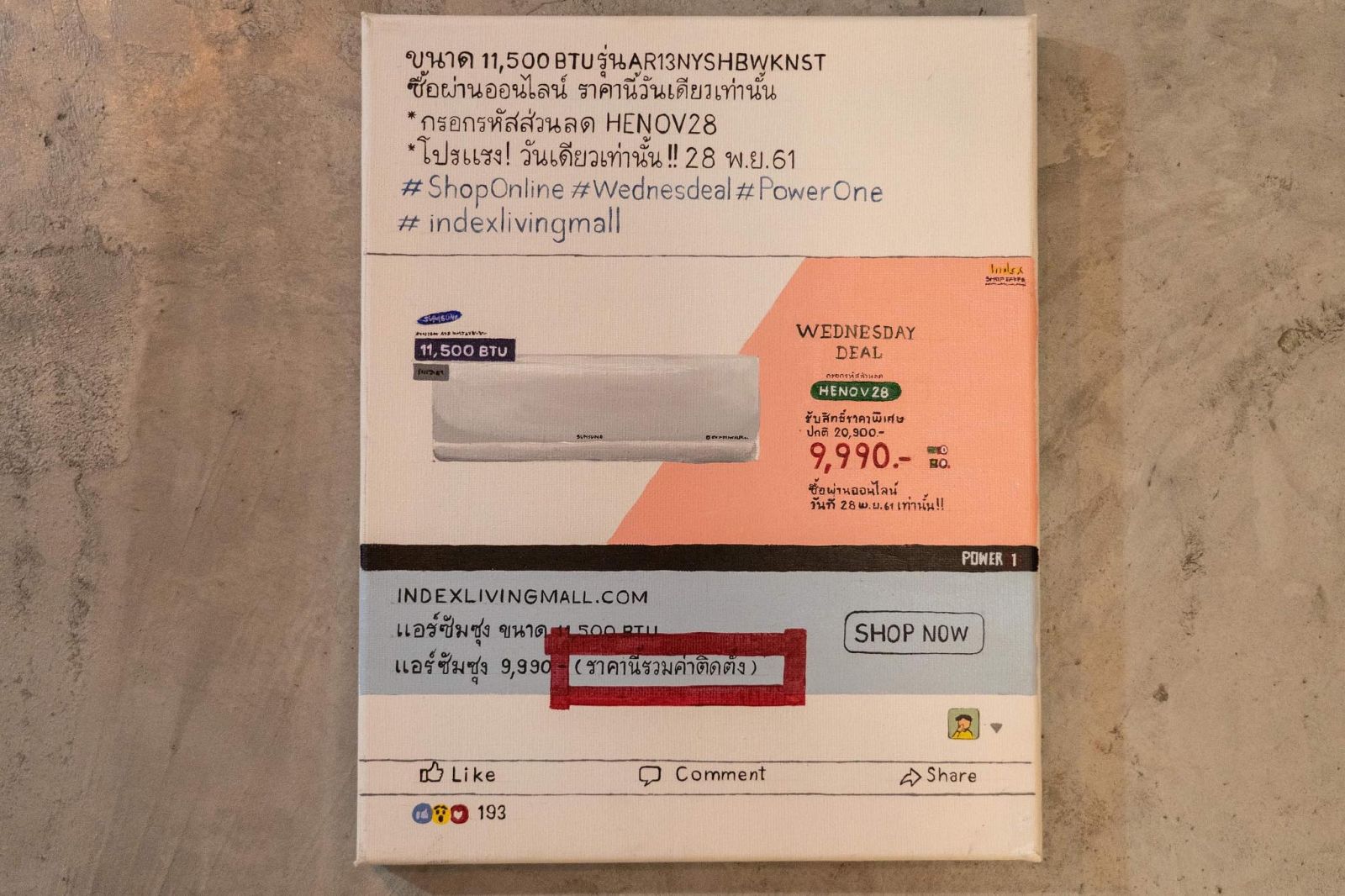

About three years ago, the Thai artist Thitibodee Rungteerwattananon purchased a small studio in a ramshackle apartment block in a working class neighborhood, on the outskirts of Bangkok. The unfurnished space lacked an air conditioner, and Thiti, as he is known among friends, saw an advertisement online for an airconditioning unit that came with free installation. As an emerging artist of limited financial means, he jumped on the offer, but received a nasty shock when the delivery crew refused to install the unit without additional cash payment on the spot. Rightly upset, Thiti posted about the incident on Pantip.com, a popular Thai message board, only to have his account blocked and his post removed. This only strengthened his resolve to seek justice, so he took his case to court and decided to document every step of the process for an art project. He won his case about five months later; however the money awarded was less than the amount spent on the air conditioner installation. And ultimately he received no compensation for the countless hours spent on paperwork and bureaucracy.

The artwork produced through this project consists of a series of trompe l’oeil paintings meticulously reproducing the screenshots of the original advertisement for the air conditioner, the post removal notice from the message board, and the documents accumulated throughout the legal process. These paintings were neatly hung in sequential order on the otherwise bare cement walls when I arrived for a week-long stay at The AIR, the informal residency program which Thiti now runs out of his studio. There was no application process, no programming, and no expectations placed upon me during my stay; I was simply given keys to the studio, so that I could crash there while checking out some art exhibitions. Far from the glitzy malls and white cube spaces of downtown, I caught a glimpse of how Bangkok’s motorbike taxi drivers and Burmese migrants live, sweating heavily as I climbed up to the sixth floor walkup every night (the elevator being permanently out of commission) before gratefully turning on the air conditioner and collapsing on the mattress in the middle of the floor.

Thiti’s work and The AIR project — encompassing both the conceptually driven paintings and the informal residency program — exemplify two interrelated themes which characterize much of the contemporary art being made in Thailand today, namely artistic production as a form of resistance to systemic injustice and the mobilization of affinity networks of artists and patrons to sustain such efforts. However, before delving into the dynamics of resistance, we must first make sense of what is being resisted: Thailand is ostensibly a democratically governed constitutional monarchy, but in 2014 the military staged a coup, then consolidated power by rewriting the constitution in 2017, stacking the national assembly with military officers, and staging sham elections. Although they vowed to stop corruption and boost the economy upon assuming power, prominent junta figures and business elites have since been exposed for egregiously corrupt acts such as poaching endangered panthers, smuggling heroin, and flaunting diamond encrusted watches for which their official income could not possibly account, all while the economy continues to sputter and stagnate. Unsurprisingly, this situation has only aggravated economic inequality, so much so that Thailand was rated as the most unequal country in the world according to a 2018 report by Credit Suisse, which estimated that the richest 1% hoard about 67% of the nation’s wealth.

To put a human face on the relationship between military rule and economic inequality, consider this anecdote from a young artist I met at Chiang Mai University last year (the artist wished to remain anonymous, as he was standing next to an installation of his artwork that was explicitly critical of the military, which could potentially get him into trouble with the authorities). He explained that he had been conscripted into the army prior to starting his art degree, as military service is obligatory for all male Thais unless they pay a fee to be exempted. The fee is easily affordable for middle and upper class families, hence only working class males are unable to avoid conscription. This young man told me that his commanders forced him and his peers to jump through a latrine into a lake of raw sewage, punishing his entire unit for the shortcomings of an individual soldier. In light of such dehumanizing treatment, it is perhaps easier to imagine why a Thai soldier snapped and killed his commanding officer this past February before livestreaming his shooting rampage at a nearby mall, killing 29 and injuring dozens.

Amid this oppressive climate in which activists regularly go missing or get gruesomely murdered, artists and other cultural workers constitute some of the leading voices in the country speaking out against corruption and inequality. The junta knows this, which is why they slashed the budget of the once publicly funded Bangkok Art and Culture Center, forcing the center to scramble to raise private funding to sustain its programming and pay its utility bills; there had been a proposal to transform the purpose-built art center into a public co-working space, but the plan was retracted following a massive public outcry. Accordingly, the support of patrons is more important than ever, including that of collectors like Eric Booth, founder of the MAIIAM Museum of Contemporary Art in Chiang Mai, and successful artists from the older generation, such as Rirkrit Tiravanija and Mit Jai Inn, who opened galleries next door to one another in Bangkok’s N22 warehouse complex, providing platforms for a new generation of Thai artists who confront injustice in Thai society and beyond.

Thiti has displayed work at both the MAIIAM and N22, but not in the ways you might expect: photographs documenting his project Thai Message currently hang inside the public bathrooms at the MAIIAM, ironically calling into question the status of Thai artists on the global stage. The project began in 2006 when Thiti visited the Tate Modern and found that there were no works by Thai artists on display, prompting him to put out a call for Thai artists to mail him artwork. He then surreptitiously installed these works inside the bathrooms at the Tate, where they remained on display for several days until the museum noticed and took them down. Thiti also has a project currently on display at N22. Titled Mass Art Project, it consists of affordable artworks (most of them priced no greater than 300 Baht, or about $9) by a variety of young Thai artists, which are not only available for purchase in the back room of Gallery Ver, the gallery founded by Rirkrit Tiravanija, but also online through Thailand’s most popular online shopping websites Shopee and Lazada. Notably, both the aforementioned projects draw upon the egalitarian Fluxus tradition of mail art, prioritizing concept over materials, mobilizing networks of like-minded artists, and bringing contemporary art outside of its conventional spaces so that it might be exposed to broader publics

Of course, exposing the public at large to contemporary art is uncontroversial unless the art in question speaks truth to power and the powers in question find out. Thiti discovered this himself when the company that sold him his air conditioner caught wind of an article about The AIR by the critic Thanavi Chotpradit, and retaliated by pressing criminal charges against him, the author, and their photographer for libel. Suddenly, he found himself facing potential jail time for allegedly slandering the company, and was forced to put up his studio as collateral for the exorbitant bail fees, lest he be thrown into prison while awaiting trial. When Thiti finally went to court, the judge could not help but chuckle when he read the case — and yet, the prosecution moved forward. The court eventually dropped the charges against the author and the photographer, but Thiti was still under threat of imprisonment until he published a conciliatory statement on Facebook, absolving the company of any wrongdoing.

Such is the convoluted nature of the justice system in Thailand, where the act of questioning corruption is typically more dangerous than the act of engaging in corruption itself. However, there remain glimmers of hope: at the end of 2019 a new opposition party emerged, and when the junta moved to block their representatives from running in elections, students bravely demonstrated all across the country in the first wave of public protest since the military crackdown of 2014. Then, this past July, over a thousand protestors gathered at Bangkok’s democracy monument dressed in black, throwing up the three finger salute of resistance from The Hunger Games, and issuing a set of demands, including that the prime minister step down and a new constitution be drafted. Since then the protests have continued almost daily while growing exponentially in scale, widely attended by both veteran protestors who took part in the Red Shirt movement a decade ago, and youngsters from Gen Z who had never been to a protest before.

In the same spirit, Thai artists band together across generations and support one another each according to their means, as they collectively resist a political and legal system which employs one set of rules for the rich, and another for everyone else. Thus, the battle over the installation of an air conditioner points to something greater: the struggle for equality, justice, and democracy for all.

David Willis is a writer, curator, and art advisor from New York, based between Ho Chi Minh City and Chiang Mai since 2015. David Holds a BA in anthropology from Columbia University and an MFA in art criticism and writing from the School of Visual Arts, New York. He previously served as a curator at MoTplus art space and as an advisor to the Nguyen Art Foundation in Ho Chi Minh City. Willis publishes regularly in magazines such as Art Asia Pacific and Art & Market. His overarching goal is to promote contemporary art in Southeast Asia.