I remember walking on the decks and bridges that connect different production sectors of Liu Wei’s factory-like studio in the outskirts of Beijing. Lyutsiya’s face is veiled by a black mask, with only her eyes exposed; it intrigues and scares me at the same time. It is 2018—I’ve just arrived in Beijing from Brussels. “In this room I am made of air and metal,” she says, obviously addressing the weight of things––yes, those things are heavy and floaty, in multiple meanings of the word. Lyutsiya works as an assistant in Liu Wei’s studio.

At that moment I am musing that the best environment for thinking about the works of Liu Wei is walking on the street, regardless of the city the streets cross, or the city they link to. Through this short recollection, Liu Wei’s material cosmos will lead the way, to arrest some thoughts and lights, as well as my memories.

Words are the change that is underway. Usually there is more than one word for any single thing in the universe, and for what is not there at all. Sometimes it could be the same word for both: for what is there, and what is not there––the word panic comes to mind. And obviously––more than one city can be seen in the same walk. Some words leap through windows, open and closed; some raze the sky; some are stuck indoors like plants in an abstract painting––cozy. Others emerge as an arcade transforming into a fountain that always arrives here at a specific moment, like a routine-driven person. Otherwise, this corner stays as another city. Look right––it is London, look left––it is Beijing. Look again––it is neither of them. It is all shadows, these permutations of a given order, even if they are made of grey car paint, glass, or aluminum board. But it is not all so fluid. Sometimes streetlights or street names stay the same; other times, a conversation partner does, or the anxiety of not recognizing anything or recognizing too much, in one extended panic loop. Sometimes a conversation partner becomes a life partner: this changes the whole landscape. Other times, a life partner becomes just a conversation partner: another tectonic shift. When Liu Wei’s kinetic Shadow series (2018) starts spinning and alternating, reminding you of something familiar, you know, it is a pattern, not just a partner or landscape at work. “How predetermined is this pattern?” you ask yourself first, and when it happens again, you turn to your neighbor: “Does it happen to you, too, that things repeat in the same order, but the range and the amplitude of their movement grow?”

The weight of things comes with expectations that grow on us when we do it in public. An artist is expected to make a statement––risky enough to shake the ground, and secure enough to preserve its own continuity, to stay reproducible. Liu Wei obviously delivers that: one can even say that while his unidentified constellation moves along calibrated tracks, it comments on the automated mechanisms of maintaining the balance of things, but then there is another smaller statement inside it, like the one you hear in bebop asymmetric phrasing in jazz. The smaller statement is heavier than the larger statement it is contained by, a splash of virtuosity bespoke by the illusion of weight and power. The power of perception, too.

As I think to myself, the subject has been slightly changing: the power of perception brings the Winchester Mystery House in California into focus. Madame Winchester was a widow of the inventor of the eponymous Winchester rifle that was deployed in many 19th century wars, but especially in the extermination of First Nation tribes in the Americas: a weapon of genocide. After his death, his widow was advised by a psychic that the best way to keep the spirits of the deceased in peace and cast away the evil created by the rifle of her husband would be to build a house and never stop building it. For decades, Madame Winchester woke up every morning with a new idea and an addition or twist in the construction: a couple of stairs to be added, or a window sealed off by a wall. The house remained a labyrinth in progress, as any progress probably is––a labyrinth, despite the idea of a gradual improvement. In order to protect the peace of ghosts in the house, Madame Winchester created a lighting system that would prevent shadows being cast indoors. Supposedly, ghosts don’t have shadows, and for them to witness shadows of living beings is a painful nightmare. “Why can’t ghosts just feel okay without having to feel human?” I wonder.

“In this room, I am made of both,” Lyutsiya laughs in response.

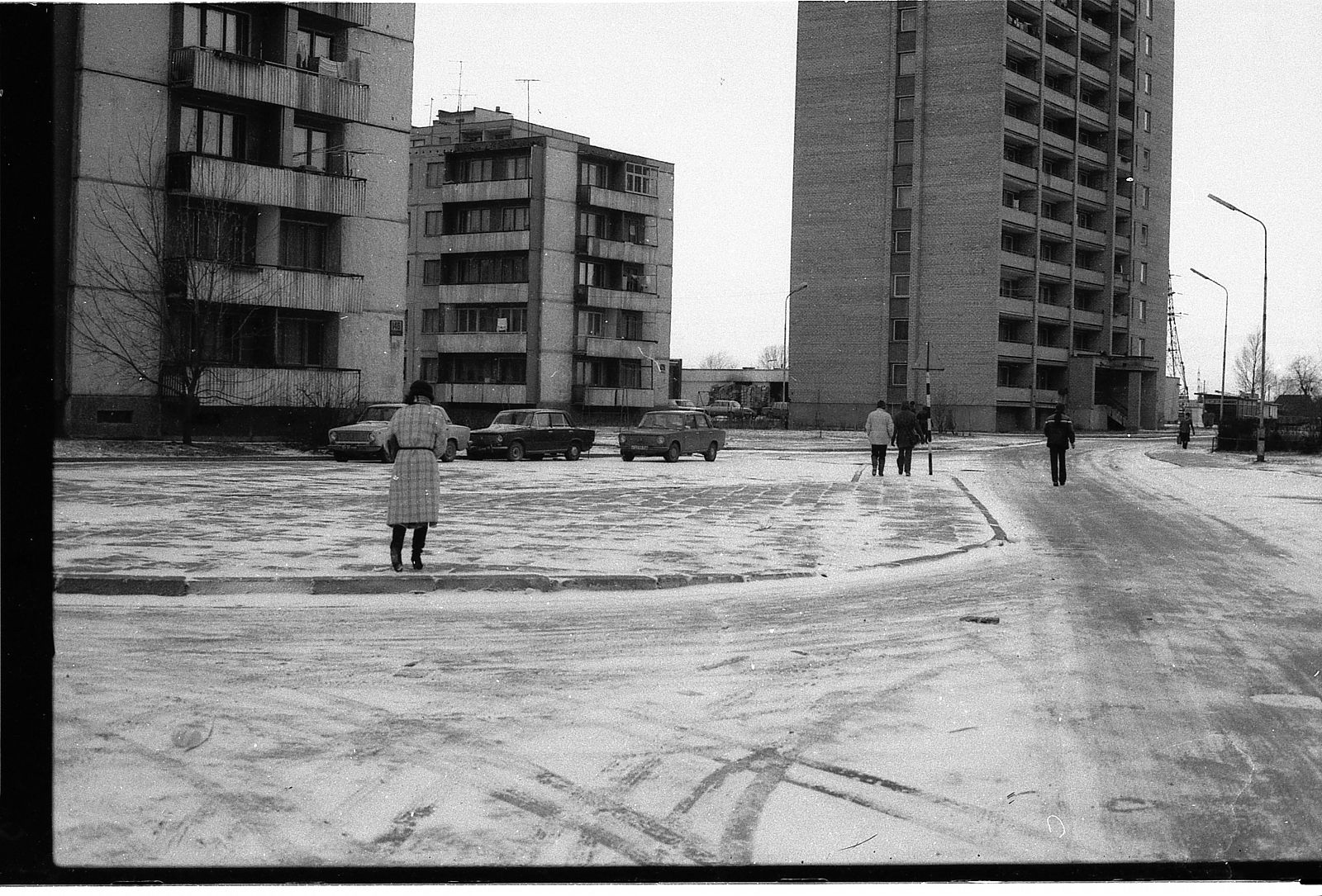

Outcast (2007) and Merely a Mistake (2009-2011) are two earlier works by Liu Wei saturated with both ghosts and humans. These ensembles are mainly made of wooden constructions, door and window frames, what previously served as thresholds between interior and exterior, inside and outside. Following the rapid growth of cities, these frames were removed from demolished buildings, collected, dismantled, and reassembled into what looks like the frozen state of a kaleidoscope: transparent, angular, laid together according to rational principles. A capsule of frozen possibilities, whose outer shell defines its own limits. The sheer volume of interior space delineated by this shell makes me think not of an individualistic interiority, but the larger interiority of a commune that existed in the same building. Perhaps it was not just one building, but a number of similar types of buildings across the city, where people lived under more or less the same circumstances, routines, and bonds. This is how I see life in a big communal building of the past: deeply connected on multiple levels, spiritual, emotional, organizational.

But I should be the last one to trust these wishful perceptions about the past. I grew up in a Soviet communal building apartment myself and I don’t even remember saying hello to the neighbors. The sense of community was enforced and thus rejected. We, as neighbors of the same building, shared a sense of mutual ignorance at best, a passive-aggressiveness bordering on hostility. Only once or twice I was invited to my neighbors’ apartments: for wrong reasons, I suppose. Once it was a man who wanted to show me his collection of plastic weapons. He looked across my shoulder to a certain void behind me, smiled widely, and opened the door. But I didn’t dare enter because his eyes were talking to someone next to me, a phantom friend, someone who wasn’t there. An extended moment of confusion, but then my mother came and none of us got to play with the plastic arsenal. Who knows––maybe that phantom person sneaked into the room? Perhaps the newly made friends also like to look at the windows of those buildings from afar and muse on the deeply intertwined sense of communal interiority, where a sense of connection to the past is excited by a sense of a harmonious future together. And then it is sealed by the artist into a massive gemstone, half time travel machine, half governmental office building, half abstract public sculpture, and half intellectual exercise.

An older flashback arrives––there I am stuck at the center of a multidimensional cosmic traffic jam at Beijing’s Dashanzi; cars are moving in the most unpredictable way, it appears as automotive chaos, but upon closer inspection from a window of my taxi, I realize that the apparent lawlessness is actually a fundamental negotiation of power through force and size, Darwinian mobility of the fittest, sturdiest, most well-equipped: a deeply sculptural action. On the other side of the memory, my mother is talking about life in the communal building in Lithuania––her description brings up something so abundant with care that I feel I need to rewrite that whole passage stemming from a wish to make a sharp statement about sociopolitical regimes; “the man with the plastic toys didn’t even live in our building,” she puts things in order. Meanwhile, I am caught by the urge to explain a certain mechanism of the world using Liu Wei’s work as a demonstration tool: something akin to quantic subatomic order, with two different energy states of the same thing, and an observer’s eye affecting what is happening there. However, alerted by the realization that evoking more than one order of things (like talking about emotional connectivity, quantic paradoxes, and the smell of machine oil at once) is also a matter of habit in the art world, I feel a need to pause. It is a binding practice, this habit, though, nothing wrong with it. But as a quest for calm, I feel a need to remove myself from the intention to demonstrate anything more abstract or more concrete than what I am looking at: Liu Wei’s metallic clusters; and “removing myself” will resonate with the surfaces of the steel that vaguely reflect and softly reject a soft erasure of one’s body.

“Was it violence I wanted to talk about?” I ask Lyutsiya as we stand on a connecting bridge of the studio.

Are you talking about the characters of this city, or the work of the artist?” she wonders.

Maybe the subject will come later, or it already has––as a twist of form, removal of a subject, or a suspension of continuity.

Raimundas Malašauskas is a curator of trust & confusion at the Tai Kwun Contemporary in Hong Kong and The Russian Pavilion in the 59th Venice Biennale. He has co-written an opera libretto, co-produced a television show, served as an agent for dOCUMENTA (13), and curated oO, the Lithuanian and Cyprus pavilions at the 55th Venice Biennale. He was also a co-curator of the 9th Baltic Triennial of International Art (Vilnius), the 9th Mercosul Biennial (Porto Alegre), and the 9th Liverpool Biennale. He previously taught at California College of Arts (San Francisco), HEAD (Geneva), and the Sandberg Institute (Amsterdam). Paper Exhibition, the book of his selected writings, was published in 2012 by Sternberg Press. He was born in Vilnius, Lithuania.